Taking Sides (or Not)

People often remark to me that conducting workplace restorative mediations must be really stressful work. My response is that compared to defending criminal matters as a barrister, mediations are a joy!

I was a litigation lawyer for just short of 10 years throughout my 20s in South Africa, initially as a solicitor and then as a barrister. I don’t believe I was ever innately suited to being a litigator. I struggled with having to represent only one party and their version. It felt for me that litigation was about winning at all costs (or shrewdly negotiating the best settlement for my client if I had an ‘unwinnable’ case). I recall a saying at the Johannesburg Bar: “a good settlement is when both parties are unhappy”. (Another saying was that “On the 8th day, God created Postponements”, but let’s not go down that rabbit hole!)

As a young and fairly inexperienced barrister, I took on a handful of pro bono criminal defence cases for the State representing black clients who were accused of major crimes (including murder and robbery) and could not afford legal representation. Due to the high crime rate in South Africa, junior counsel could be appointed to take on these types of cases. In those days during apartheid, the death penalty was still being imposed, although thankfully there was a moratorium on its implementation.

The day I knew I had to leave the law and change careers was due to one case which, ironically, was both the high and low point of my legal career:

My client was a 19 year old man who was the second accused in a murder and robbery case. During the consultation with him and his mother prior to the trial, I noticed that he was shy and reluctant to speak to me in front of his mother, or at all. I took his mum aside and implored her to speak to her son overnight to encourage him to tell me what had happened in order to be able to defend him properly. I also expressed to her that I was concerned that he may be reluctant to admit to anything due to feelings of fear or shame. The next day he admitted to me that he had been involved in the robbery, but did not know the first accused had a gun or would use it.

I went to the State Prosecutor and offered her a plea of guilty to robbery on behalf of my client. The first accused had disappeared and was never caught, so the State’s case was singularly against my client. The State Prosecutor rejected my client’s plea offer and the trial went ahead on both the murder and robbery charges.

By the close of the State’s case, I realised that they had probably not established proof beyond reasonable doubt. Although I had spent considerable time (through a Zulu/English interpreter) preparing my client to give evidence in court in his defence, I now needed to explain to him that I did not want him to give any evidence at all. After much deliberation and consultation with senior mentors at the Bar and a shockingly sleepless night, I opened and immediately closed my case without leading any evidence. My client was acquitted of both charges.

I will never forget that day. I walked down the stairs outside the court building and felt the sunshine on my face. I felt absolutely no remorse that a young offender was free. I had won! I felt exhilarated. But I also realised that this exhilaration came from beating the system, and that to have a successful career as a litigation barrister I would need to get more comfortable with taking sides in order to win!

On arrival in Australia, I requalified as a lawyer to be admitted to practise here (so that the 10 years counted for something). However I knew I was never going to practise law again. So I elected to not maintain a practising certificate and often need to tell clients that I am unable to give them legal advice for this reason.

Our Human Inclination to Take Sides

As human beings our penchant to favouritism and to take sides is fairly natural – we resonate more with some people than with others, and our loved ones, friends and close colleagues expect us to side with them as a demonstration of support.

I acknowledge that I sometimes annoy friends, family and clients because I naturally see situations from a multitude of perspectives and can’t simply agree with them out of blind loyalty or because it’s what they want to hear.

I also often acknowledge to clients and restorative mediation participants that it is easier to have perspective when it comes to other people’s lives but much harder to do in our own lives. This is the value of honest and kind feedback.

Impartiality in Restorative Mediations

Ten years ago I started a consultancy practice and designed a Restorative Mediation model which gets astonishing results. When I follow up after a restorative mediation, clients are often amused when I tell them that even I am astonished by its results! I have now conducted over 290 restorative workplace mediations.

Being impartial as a workplace mediator is crucial. Clients often offer to brief me on the conflict beforehand. Depending on the circumstances this is sometimes necessary. Mostly I prefer to start a restorative mediation without a briefing to be able to inform both participants that I’ve had no briefing so I am not influenced by the organisation’s perspectives.

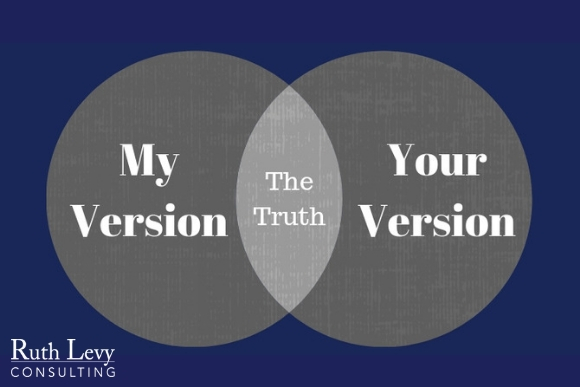

During mediations I can feel that participants want me to take their side. However they gradually come to realise during the process that I won’t and can’t do this. My compassion for their respective stories or feelings does not mean I’ve taken sides as I believe that ‘the truth’ in most workplace conflicts lies somewhere in the middle of two inter-subjective versions.

I am mostly met with much scepticism at the start of a restorative mediation process, particularly when a participant has been through a previous and unsuccessful different type of mediation. On occasion I have even needed to challenge a participant by inviting them to tell me at the end of a process (or in 6 months’ time) that it was an absolute waste of time! I will gladly hear this feedback if it’s their truth. Until then, I ask them to:

· engage with the process 100% as they have everything to gain and nothing to lose

· suspend their cynicism for the duration of the process; and

· be willing to be surprised!

The Restorative Mediation Approach Embodies Impartiality

Unlike an adversarial litigious approach, a restorative mediation embodies impartiality because:

1. It’s based on the premise that conflict is co-created: Irrespective of either party believing at the start of the process that the other person is completely to blame, both people participate in the conflict to some degree, even if it’s to ‘shut down’ or withdraw from the other person and completely ignore them.

2. It’s not about being right or wrong: As humans we recall facts and incidents through our subjective filters and our assumptions can often be wrong. To organise our experience we ‘build cases in our heads’ about others. Metaphorically, we have filing cabinets in our minds with folders about others. When others say or do something/anything in a certain way, this becomes additional evidence of our existing believe system about them. I appreciate that the participants’ respective subjective versions are real for each of them, however letting go of needing to be right is an important component of the process.

3. Its focus is not on the facts: Although I hear the participants’ respective stories and versions at great length during the individual sessions on Day 1, the combined session on Day 2 does not require an arduous unpacking and examination of the facts to determine ‘the truth’ as it is not an investigation. Instead I commence the combined session by carefully and neutrally briefly summarising (in front of them both) what they shared with me on Day 1 - their respective stories, versions, experiences and feelings.

4. It’s relational in nature: Essentially the process involves a lateral healing of inter-personal working relationships, irrespective of reporting lines. It is less effective if the cause of the conflict is under-performance by one of the participants and the organisation is unwilling to address this. Further, if a participant is not directly impacted by the other’s behaviour but has taken on the matter as an advocate for other staff, their motivation to genuinely resolve relational issues directly between them might feel like a betrayal of the other staff.

5. It’s a 'no blame' process: The combined session is framed around a “no-blame” safety rule so it is not an opportunity to blame the other as I believe that real resolution comes from looking at our own behavior, rather than persistently blaming another.

6. It’s restorative in nature: It requires self-reflection, accountability and acknowledgement of the value for the other and how both participants may have let the other down. When we have been in protracted conflict with another, hearing how they value you and how they might have let you down creates a space for softening and compassion towards the other. This is the most dignified and graceful way to resolve conflict.

Not a day goes past when I regret my decision to change careers. I am so grateful for the work that I do and I am deeply committed to it. As a participant in one of my restorative mediations recently described it: “healing the world, one conflict at a time”.